First, a confession: I don’t believe in Sound Studies. Okay – perhaps that needs some qualification. Rather, I do wholeheartedly believe in the study of sound: as a budding musicologist trained in historical enquiry, archival excavation, score-based analysis, hermeneutic possibilities (and many years ago now, I was actually able to play a couple of instruments!), organized sound has been my object of study for around a decade. But Sound Studies as a field is so all-encompassing, so boundless (Mara Mills and Mark Butler bring with them at least seven disciplinary associations, let alone the audience in Holden Chapel), that whilst I am excited by the possibilities, I am also confused about where to position myself, what I have to offer and what really constitutes the study of sound.

In the midst of this confusion, unease, suspicion even, I wish to highlight a couple of points of interest to me, which came out of the fifth installment of the Sawyer Seminar entitled ‘Hearing Through The Body’.

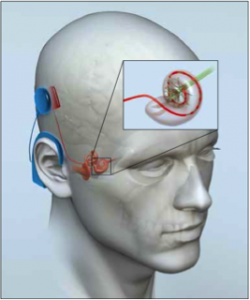

Mills’ paper re-envisions the trajectory of biomedicalization usually invoked in relation to deafness. Mills’ previous explorations into the history of the cochlear implant ‘tended to adopt a history of medicine frame, arguing that telephony was significant mainly for the transfer of equipment, components to the fields of psychology and otology’. In this, the final chapter of her forthcoming book, however, she emphasizes the emergence of the cochlear implant ‘within a telecommunications milieu as well as a medical one’ resulting in what she terms the ‘biotechnification’ of hearing. By highlighting the role of telecommunication technologies, Mills presents the history of the cochlear implant as an attempt to render greater control over hearing rather than as a solution to the ‘problem’ of deafness. By the end of her history, hearing, generally acknowledged as a passive, or at least uncontrollable, sense is posited as a powerful means of communication when in the hands of the cochlear implant and its affordances.

Butler’s second book, of which this paper also comprises part of the final chapter, marks a move away from isolated, record-cum-score-based analysis of EDM towards performance studies. Butler’s concern with the live experience of EDM in which DJs create original music in the moment has lead him to identify ‘musical technologies’ of repeating, cycling, going, grooving, riding, transitioning and flowing. Repeating is the umbrella technology, whose temporal rather than spatial (the historical tendency is to conceptualize repetition as static, the graphic representation of a circle epitomizing this reductive attitude) quality is emphasized through performance. In re-envisioning these musical characteristics, ‘principles of design’ (p.244), as technologies, Butler emphasizes the affordances, which ‘facilitate the freeing of recorded sound within performance and its creative refashioning through improvisational actions’ (p.250). Ultimately, this re-envisioning usurps the tendency to save repetition from itself by finding the hidden nuance or variation and bestows this most fundamental of musical devices (and its relatives) with a positive persona.

Media. Mediation. Technology. (Transduction. Embodiment. Affordance. Constraint. Interface.)

Both Mills and Butler are concerned with re-envisioning stories previously told, which comes with a certain amount of re-defining and re-labeling. Whilst I would describe repetition as a musical or compositional device, Butler’s use of the gerund is intended to signal its new identity. Butler’s argument is built entirely on the understanding of a technology as a means of achieving a desired outcome. The materiality of technology, whilst still invoked by the object of the vinyl record, is ultimately ousted by the understanding of technology as a process. Whilst for those well versed in Sound Studies and its component disciplines, for me, this is a big ask, especially when the new label is so fraught with possible meaning itself.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Feeling as confused as me? Jean-François Augoyard and Henry Torgue discuss in their volume Sonic Experience (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005) attempt to provide a detailed glossary of key terms.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

‘Mediated Technologies Take 2 or Embodied Hearing?’ By posing this question, Mills highlighted two ways in which we might perceive our experience of her talk, encountering the research and ideas presented in her paper ‘Earless Hearing’ a second time round, in a new format, with the author at the helm. What may at first appear as a binary, however, is ultimately mere tautology. When Sindhumathi Revuluri asked the speakers to revisit this question – ‘what the difference really is there, where’s the division and what are the stakes?’ – Mills confessed: ‘I don’t really know what ‘mediated technologies’ means’. Mills discussed the way in which Media Studies and Technology Studies understand their respective nouns in similar terms, bringing about a convergence of meaning. Butler asserted in his response, all performances are mediated. It would seem that if we understand all processes of doing as ‘technologies’ and all activities as mediated, ‘mediated technology’ becomes something go f a catchall. Upon reflection, Mills concludes: ‘Embodied listening is a media phenomenon’ (her emphasis).

Although I felt somewhat reassured by this seemingly categorical statement in support of which Mills emphasized the mediality of skin, hair, air, all of which conduct sound in someway, her discussion of speech seemed to undermine her own logic. As an introduction to Media and Communication Studies at NYU, speech provides the point of departure as the ultimate medium. According to Mills, the mediality of speech lies in the fact that it is learned, a construct. But skin, hair, air are not learned or constructed. They are, dare I say, natural. Can natural and man-made, learned and inherent objects, concepts, modes of expression all occupy the status of media? Surely yes – but the possibility of these co-existing or non- binaries, which admit everything, highlights the difficult of re-envisioning inherent to the enterprise of Sound Studies. `

How can we talk meaningfully about sound?

This terminological overload is undoubtedly part and parcel of the challenge in talking – or rather writing – about sound. As Graser (the deaf expert listener involved in the development of the cochlear implant with House) notes: ‘It is difficult to compare what you hear one time with what you heard one month or a year ago. It’s sure too bad that what I hear can’t be recorded’ (Mills, p.30).

= = = = = = = = = = =

More Mills…‘What Should We Call Reading?’ Flow, Volume 17 (December 2012) and ‘The Audiovisual Telephone: A Brief History’, Handheld? Music Video Aesthetics for Portable Devices, ed. Henry Keazor (Heidelberg: ART-Dok, 2012), 34-47).

= = = = = = = = = = = =

I think this difficulty has something to do with the sensory conflation that occurs in the experience of sound. As Michele Friedner and Stefan Helmreich emphasize in ‘Sound Studies meets Deaf Studies’ (Sense and Society, 2012), disciplinary boundaries construct the discreet separation of the senses. Their discussion of haptic hearing, an important topic in the Music and Torture seminar, highlights the ways in which sound is felt. In ‘What Should We Call Reading?’, Mills suggests that listening to an audiobook may be redefined as reading, as an ocular activity. It is universally acknowledged that impairment of one sense tends to increase the sensitivity of another, which allows for multi-sensory engagement with sound.

That said, it was in the experience of listening to Phon.o’s locked grooves that Butler’s theory of musical technologies really hit home. Can words replace listening? Terminology is only part of the answer. As Suzanne Cusick’s poetic paper with its embedded MP3 files attests, the written word can fail us. It is imperative that scholars of Sound Studies explore new means of knowledge dissemination.

Hayley Fenn

I would like to thank Mara Mills and Mark Butler for taking the time to meet with me and my colleague, Matt Blackmar, to illuminate their own work further and to discuss ideas about our ensuing project. I am riveted by the fascinating work of both scholars and hope that my own work can contribute something meaningful towards the field of Sound Studies – despite my trepidation.

Leave a Reply