On November 18th, the School of the Museum of Fine Arts hosted the second lecture in the ongoing Intonarumori series, running in collaboration with Harvard’s Hearing Modernity seminar. This time around, we were joined by Christopher DeLaurenti – described on his website as a “sound artist, improvisor, and phonographer” currently based in Virginia. Christopher DeLaurenti’s work spans across mediums – engaging forms of recordings, scores, writings, and otherwise. He is an influential figure in the world of sound art and discourse, and it was very exciting to have him share his thoughts with our community. Christopher began his lecture with a statement, as follows.

“Listening is about giving the gift of time, which is our mortality, which is something ever so precious.”

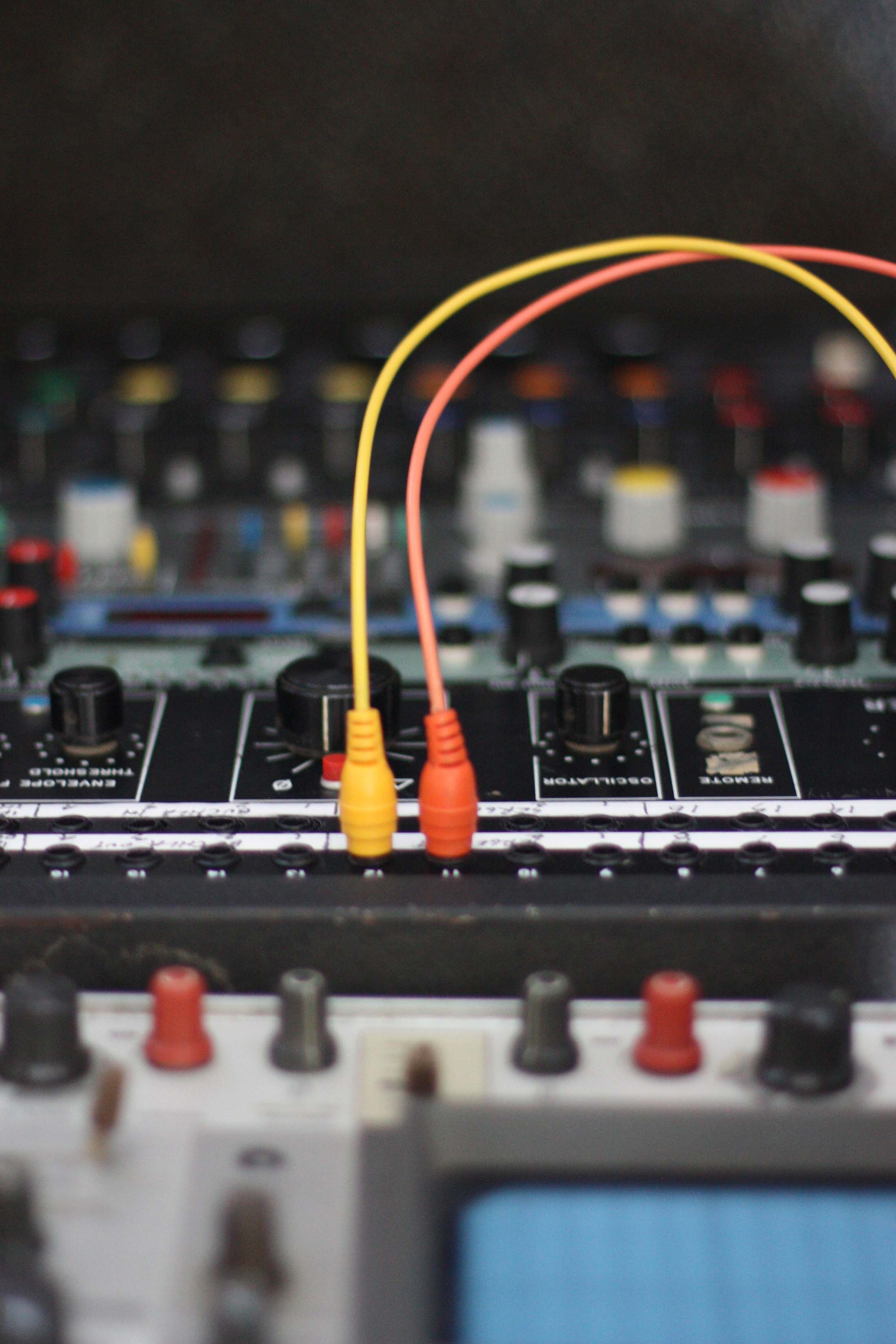

DeLaurenti broke his lecture down into four sections, the first of which was focused on his own introduction to sound. He began with a background on himself and his musical past. Christopher told a story of his grandfather, who was employed as a coal miner, and who had the educational training of a fourth grader. Through self-motivation, DeLaurenti’s grandfather was able to teach himself how to repair a multitude of instruments, and make a functioning business out of doing it. Upon his demise, Christopher inherited a vast array of dismembered and broken instruments, and through inspiration from the works of Harry Partch realized this “pile of shit” he inherited could be a symphony. Partch, DeLaurenti believes, was interested in the creation of a work, by the creation and understanding of the tools. Furthermore, Partch was creating through an understanding of his place in the world – all of these being extremely important parts of DeLaurenti’s practice. Christopher spoke of his first experience with a reel-to-reel tape recorder at age 13. He spoke of the labor he was introduced to by way such technologies – the cutting and the splicing of recorded material. How the tape did not bring sculpting and shaping of sound to the world – it merely made it tangible. That this sculpting and shaping starts with listening.

Next, DeLaurenti spoke on field recording, in opposition to recording in a studio. The field is an unstable place, a place you do not pay to go to – in some cases, you break into. Often, Christopher stated, there is no assistance. It is a place of instability – it doesn’t rain in the studio. The field is where the fundamental nature of the work is threatened. This threatening can arise in the form of unforeseen events. Christopher gave an example of a common intervention – the “hey, are you recording?” of an interested passerby.

DeLaurenti then began on a compressed historical overview of field recording. The field recording became useful and made its debut in the works of Pierre Schaefer – most notably 1948’s Railroad Study. But Christopher questioned this piece, taking note of the fact that Schaefer allegedly asked the engineers and conductor to “improvise” according to his instruction. Out in the field, DeLaurenti stated, you don’t normally ask people to do things. As he further noted, at this time field recordings were still considered as sound objects; as source material. The field recording was not considered art in itself. So in response, DeLaurenti presented an excerpt from Luc Ferrari’s Presque Rien No. 1. This piece angered Schaefer at the time of its release, as it presented field recordings pretty much as they were recorded. The juxtaposition of multiple recordings, Christopher stated, is what is crucial in this work.

Luc Ferrari – Presque Rien No. 1 (1 of 3)

Later, Christopher DeLaurenti posed the question – what can you do in the field that you cannot do in the studio? His answer to this: you can fail by yourself. He presented an excerpt of a piece by Anne Holmes, titled Wood on Wood on Water – currently only available on this SFU 40 compilation. DeLaurenti put focus upon the instability of the field, that you can hear within the recording itself. He followed this with another excerpt, from Barry Truax’s Pendlerdrøm. In this piece, the use of digital processing is an attempt to transport the listener into another place – to illustrate the commuter gradually falling asleep.

Christopher then spoke about exactly where he is coming from. He spoke of phonography, for it is how he found his artistic voice. Furthermore, he advocated phonography as a solid entry point, for it is a little different than field recording in DeLaurenti’s opinion. Phonography admits the presence of the recordist – the recordist is not separate from the recording. As DeLaurenti put it, “you can live in the work.” Phonography also makes use of multiple fidelities, for different fidelities capture things in different ways. Contrary to popular opinion, DeLaurenti stated that “fidelity is a false god.” Phonography makes the use of the same source material as field recording, but the listener can recognize the material. He claimed the growth of phonography to be tied to two historical events – the creation of the portable minidisc in the mid-90s, and the advent of the Yahoo discussion list in 2000. DeLaurenti sees this trajectory continuing, led by the ever-growing and democratizing ability to record sound on mobile devices.

But why record protests? – DeLaurenti asked himself. His first answer was this: because the source material is fundamental and entire to the work – and that this is a conscious choice. There are people out there putting their lives on the line, Christopher stated. This idea of life is defined very broadly – he made the point that if you took part in any sort of protest past the late-90s, you are on camera. That footage is recorded and catalogued, never to be erased. DeLaurenti believes this to be a profound risk. He then presented an excerpt, from N30. It may be hard to tell who’s who in this recording – this is very important. These recordings, according to DeLaurenti, are not a primer on issues, they are a point at which to jumpstart further investigation… if you see fit.

N30: Live at the WTO Protest November 30, 1999

Christopher then went on to speak about ecology, and its relation to art. He is of the opinion that one of the big diseases in art of the second half of the 20th century is that of internationalism – that everyone should be able to experience and understand a work in the same way. He was quick to admit that his work is primarily for English speaking audiences, and that this is not problematic. For the work effects those who can understand it – the speech, the political climate, the protest itself. DeLaurenti is very much interested in connecting to what people know or might know, in the culture in which they are enveloped.

Live in New York at the Republican National Convention Protest September 2 – August 28, 2004

In this recording, DeLaurenti put focus upon the fidelity ranges apparent within the work – how they aid the expression, and propel the drama. The edits here are intentionally both noticeable and unnoticeable. Then there is the improvisation that comes with the police officer’s repeated phrase, “please step back. please step back…” – DeLaurenti pinpointed this as a performative action. Christopher compared this recording to N30, as an example of how the tactics have shifted and changed. “Call me on my cell phone” a police officer tells his colleague, as he knows that police transmissions are now tracked, recorded, and even intercepted.

As a final point, DeLaurenti addressed the issue of privilege – for this is something the Occupy Wall Street movement looked to speak about. He spoke about his privileged strengths as a 6′ 4″ white male, that no police officer is necessarily looking to mess with. But he also spoke about his weaknesses, as an easily spotted individual, as someone sometimes mistaken for a cop. As a person who cannot sneak under barricades or blend into a crowd. After sharing an excerpt from an in-progress work on Occupy Wall Street, he followed with a quote from Claude Levi-Strauss:

“Exploration is not so much a matter of covering the ground as of digging beneath the surface: chance fragments of landscape, momentary snatches of life, reflections caught on a wing – such are the things that alone make it possible for us to understand and interpret horizons which would otherwise have nothing to offer.”

To conclude, DeLaurenti left us with one final statement, summing up the entire presentation in one swift mark.

“So the central question is: You’ve got a bunch of people yelling on the street – why are they here? What are they doing? Do these works help impel questions? Do these works help people ask why, and to ponder what goes on? Ultimately, I hope that these works become like the military – that they put themselves out of business. That they become obsolete and quaint documents.”

– by Simon Remiszewski

Leave a Reply