Joseph Auner, Tufts University

Response to Trevor Pinch and Flagg Miller, Hearing Modernity (November 25, 2013)

In these two exciting and stimulating papers Trevor Pinch and Flagg Miller explore how the experience of sounds and our sonic environments are shaped by the stubborn materiality of specific technologies as nodes in the complex socio-technical networks we inhabit. They demonstrate ways in which the peculiar sonic signatures of devices like the portable cassette machine and the Moog synthesizer can become sources of meaning; just as with human relationships, it is often flaws and limitations that are the source of the deepest emotional attachments.

By way of a response I would like to follow up on Flagg’s metaphor of the “genie and the bottle” to think more about the rich interactions of sound technologies and the sounds they produce. Both essays offer important insights into what it can mean to listen to sounds, as Trevor writes, as they “are embedded and entangled with, and mediated by, material and technological devices, and [as] listening practices and other bodily practices co-evolve with these new sorts of sonic technologies.” I was particularly interested in Flagg’s discussion of how the sound of the cassette came to be heard as ascetic and edgy, as well as Trevor’s concluding section on the emergence of what he calls generic sounds associated with specific synthesizers, musicians, and pieces of music. At the same time, their insights challenge everyone attempting to write about sound and listening to continue to develop a richer shared vocabulary for helping us to hear and describe sounds together with their histories and their social meanings.

Reading these essays it also became clear just how central individual backgrounds and experiences are to our responses to the sonic genies that emerge from our devices. Trevor’s account of the strange paths that the synthesizer took in becoming a marketable instrument took me back to my own childhood obsessions with synthesizers, starting when I was around 14 with an unusual presentation I heard of the first portable synthesizer, the EMS Synthi A, that an adventurous church organist arranged at a bible college in Springfield Missouri. Flagg’s discussion of Osama Bin Laden’s cassette collection motivated me to dig around in my own basement where I came across THIS cassette with some primitive multi-tracking using two cassette decks from a year after I graduated college. Through the hiss, wobble, and murkiness that comes from multiple copies without noise reduction, you can hear the sounds of my ARP Odyssey synthesizer, and then a strange kind of accidental collage as the original sounds on the cassette suddenly emerge. This happens to be a recording of a choral rehearsal at the New England Conservatory where I was working at the time as recording engineer, suggesting that this might be a purloined cassette from NEC that has charted a unique trajectory over the last 30 years to find itself here today. [PLAY CASSETTE–listen to podcast for actual recording]

Flagg does a brilliant job in helping us hear and understand all the ways a cassette tape and portable machine like this, and all the intentional and unintentional sounds they transmit, could be reimagined as a form of embodied memory, social collective, and ascetic resistance to the west. I would be interested in hearing more details about the ways in which specific sound qualities could be heard as ascetic and as a guarantee of authenticity of accurate oral transmission. In other words, can we hear different types of noise and hiss introduced with every copy, or the specific sonic markers produced by the microphones and small built-in speakers that could be compared to what you say about the individual markings and physical qualities of the tapes, with cartridges worn smooth over many years of use, labels ripped off and new ones attached. Where you write of the “edginess” of the cassette sound in contrast to the “professional and seamless flow of westernized global media,” I couldn’t help thinking, as a Schoenberg scholar, that perhaps the word “dissonance” could also be useful in characterizing the sound of the cassette as oppositional and dissident in various contexts and narratives of progress, modernity, consumer culture, and mainstream and margin.

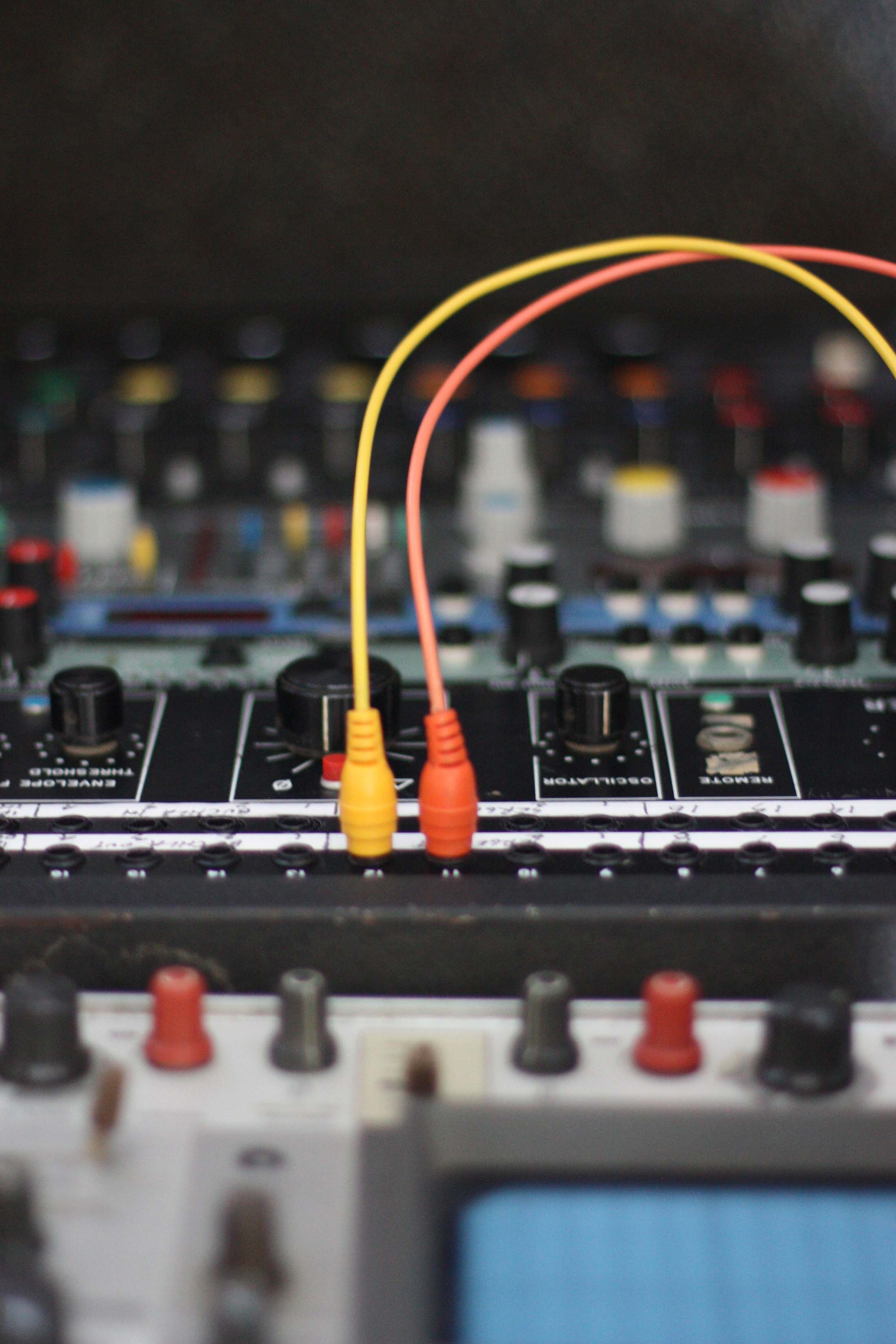

My question for Trevor concerns his notion of “generic sounds” and “generic performance practices” through which certain timbres and ways of playing associated with the Moog synthesizer became standardized and commodified. This was especially the case with the rise of digital synthesizers, which due to their complex interfaces resulted in users relying increasingly on rise of banks of preset sounds; as Trevor notes, these presets often included various “Moog” sounds. But keeping in mind the notion of the genie and the bottle, I wonder if rather than “generic sounds,” with its implications of reduction, stabilization, and closure, if the phenomenon might be described better as “emancipated sounds.” We can see this vast explosion of timbres and the development of new non-keyboard interfaces in music production software like Reason. Such programs also make vividly clear the ways in which the analog devices continue to shape the digital realm; note the intense interest in capturing the look and touch of older equipment; the synthesizer also has a familiar layout based on elements from the Minimoog and the ARP Odyssey. As the labels suggest for the huge sound archives that are provided with such software synths, these samples summon up not only the synthesized sounds, but specific devices and the musicians who used them. But with the modular synthesizer we can see how all the parameters of wave form, filter, and dynamic envelop are defined to shape the sound, and thus to allow us to modify it further. Every one of these sounds might thus be thought of as both the genie and bottle offering users a kind of authority and revelation as well as the starting points for the creation and circulation of new sounds with their own emotional and social resonances.

Leave a Reply