Trevor Pinch’s and Flagg Miller’s panel reminds us that technologies of sound mediation (and their histories) are socially mediated and culturally situated, their uses contingent on contexts and their users. In this brief essay, I wish to revisit the Sawyer Session through the filter of my youthful experiences with audiocassette recorders and analog synthesizers, in an effort to illustrate what Charles Hirschkind describes as “an approach to the question of the sensorium not from the side of the (modern) object and its impact on the possibilities of subjective experience, but rather from the perspective of a cultural practice through which the perceptual capacities of the subject are honed, and, thus, through which the world those capacities inhabit is brought into being, rendered perceptible.” (“The Ethics of Listening,” 623–24).

Some years ago, I learned that my generation had been dubbed the “Millenials” in the race by market researchers to define the 18–34 age demographic of media consumers most coveted by advertisers. Wikipedia now describes this group as comprising people born in the span between the early 1980s and the early 2000s. Yet, in terms of generational experiences of sound mediating technologies, the eldest in this cohort and the youngest among them are worlds apart. Those born most recently never knew Napster, much less an audiocassette recorder. In fact, in the era of “cloud” storage, Millenials born after 2004 may well come of age oblivious to recordable media altogether. The eldest, by contrast, lived through multiple cycles of media innovation and obsolescence. I’m one such Millenial, born in 1984. Today, on my thirtieth birthday, I can recall among my earliest memories the exhilaration accompanying occasions when my parents rented a VCR from the video store so our family could watch Star Wars. During my last visit home, by contrast, I helped my mother set up her streaming Netflix account.

I was in kindergarten when I received my first audiocassette recorder. I remember using it for a single purpose: to record music from the radio. My relationship with audiocassettes was an intensely private affair, the rainy-day adventures of a housebound child. I made mixtapes by myself, for myself, and listened to them via the splendid isolation of the headphones of a Sony Walkman. The process of making them was, in many respects, more important than the result, and they were summarily discarded not long after, winding up in shoeboxes, in closets, and, eventually, in dumpsters. Produce. Consume. Discard. If my personal audiocassette recorder and Walkman afforded me a hermetic privacy in my listening practice, this isolation, in turn, insulated me from an awareness of genre boundaries or the social and political implications of various popular musical styles and artists. Accordingly, “My First Mixtape” ingenuously juxtaposed Tupac Shakur, Genesis, Bryan Adams, and Jimi Hendrix. But the consumer-technologically mediated soundscape of my early years was also significantly a product of interstellar combat: the sounds of Star Wars interpolated with the 8-bit bleeps and bloops of my Nintendo Entertainment System.

Had Osama bin Laden come of age in the United States, he would have likewise straddled a generational divide, between the Baby Boomers and their first-born progeny, “Generation X.” Curiously, mixtape production represents a tenuous point in common between my life experience and that of the late bin Laden. Born in 1957, Bin Laden’s teenage years followed closely on the heels of the widespread popularization of portable audiocassette recording technologies, of which he was an “early adopter.” Flagg Miller reports how, as a high-school student, Bin Laden produced a mixtape of “Islamic anthems about piety, proper devotion and Palestine and had distributed it among friends.” (“The Genie and the Bottle,” 11) By the time I was immersed in the sounds of imagined interstellar combat, however, Bin Laden was working tirelessly to ensure victory for the mujahedeen in a real-world conflict in Afghanistan.

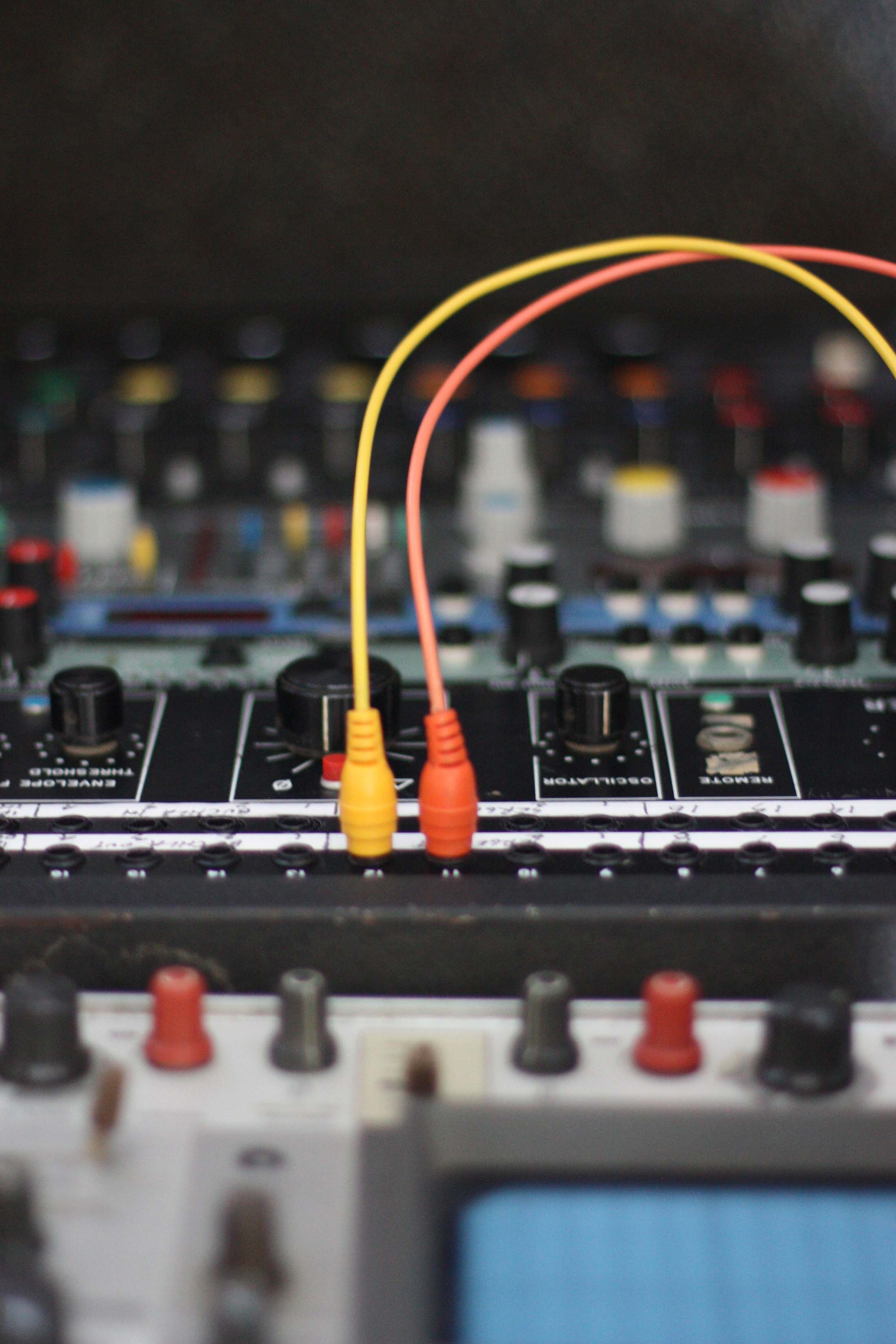

By the time I reached high school, audiocassettes had been eclipsed by recordable compact discs. Napster debuted during my freshman year in high school, and the company filed for bankruptcy the week I graduated. In college, my friends and I feverishly shared .m3u playlists—the closest thing we knew to the “associations and opportunities for social exchange” afforded to Bin Laden and his compatriots by the audiocassette collection Miller uncovered in Kandahar. And, curiously, it was during my senior year in high school that my relationship with putatively outdated consumer technologies of sound mediation came full circle: I purchased my first analog synthesizer—not a MiniMoog (with apologies to Trevor Pinch)—but, rather, its polyphonic successor, the Sequential Circuits Prophet 5 (1978-1984).

Analog synthesizers like the MiniMoog, Arp 2600, and Prophet 5 were not only increasingly prevalent in Western popular music of the 1970s and 80s, but became essential to the work of film sound effects designers. Together, both groups crafted the intergalactic sounds of my childhood, from the squeals of R2D2 to the squeals of Keith Emerson’s Moog. Before I knew E.L.P., however, I had become cognizant of the “Moog sound” (without yet knowing it by name), via Death Row Records’s singles like [then] Snoop Doggy Dogg’s “What’s My Name?” (1993). Expanding upon Bourdieu’s notion of habitus, Hirschkind writes of how “a habitus may outlive the material conditions that give rise to it by renewing, reinforcing, and adapting the practices of social and individual discipline that sustain and anchor it.” (“The Ethics of Listening,” 625). Such an understanding helps me explain how I came to know (and love) “the Moog sound” before I had ever laid eyes on an analog synthesizer, or how Osama bin Laden’s tape collection, as an archive, displays both the vagaries of fundamentalist Islamic strictures surrounding audiocassettes and the biographic importance of a history of aural experience. Ultimately, Trevor Pinch shows us how the history of technology need be understood via its social construction. At the opposite end of the life of such devices, Miller and Hirschkind help us broaden our understandings of their life cycles and afterlives, from social impacts to the shaping and disciplining of the individual sensorium. In this respect, each technology offers an apt, albeit blunt, metaphor for their scholar’s respective contributions. A synthesizer generates sounds, and its historian studies how it came to generate specific sounds, while recordable media capture and store sounds, inviting study of what these traces tell us about aural subjects, past and present.

Leave a Reply