When thinking of studying sound, or of hearing modernity, the mind tends to shift almost immediately to that of sonic environment. R. Murray Schafer’s fundamental text The Soundscape provided a fascinating examination of how sonic environment defines our living situation; some “keynote” sounds are so ingrained as to be “rarely listened to consciously by those who live among them, for they are the ground over which the figure of signals becomes conspicuous. . . [they] are, however, noticed when they change.” (Schafer 60) As such revelations have reached the public, it has become more and more common to hear of cities, towns, and tourist destinations as having a distinctive “sound,” as much as having a particular architecture or cuisine. The din of the big city can be a determining factor in keeping people away from it; on the contrary, friends reared in urban environments have similarly reported not being able to get used to the oppressive quiet of the country. Modernity specifically tends to conjure up aural images of machinery and human and architectural density, more recently of computer technology and the ubiquity of amplified sound in businesses, streets, and on persons. In the mid-70s, an entire genre of music, “industrial,” was so labelled for its acutely sonic kinship to a broadly modern phenomenon. Almost in parallel to the increasing density of our sonic environment, there has grown an interest among scholars in probing the origins, politics, meanings, and effects of the sound that surrounds us, more and more, all the time.

Another impetus for studying sound seems to have come from the study of its bastard nephew, music. One of the most heartening things about a music department’s hosting of this particular seminar is how unlikely one would have been to agree to do so in the past, and how that sort of restrictive scope in the study of music led to sound studies gaining more solid footing in increasingly post-colonial academia. For the first ninety or so years of modern liberal arts education in the United States, the study of music meant the study of classical music, much like the study of literature was that of Great Books. As the advent of critical theory in other humanist disciplines began to expand the scope of scholarly study, music (somewhat grudgingly) began look to critical theory as well; with, for example, music theorists looking to phenomenology, and musicologists looking to gender studies. But perhaps most critical to the study of sounds themselves was the rapid expansion of ethnomusicology, which not only exposed academia to different musics, it brought to music departments a laundry list of ways of thinking about and experiencing music that were much different from the Western classical situation. There came to Western ears far more to tell of societies (contemporary and past) in which the boundaries between music and daily life were not so clear; where purposeful noise was integral and not polluting. In addition to these, scholars began to turn ears to contemporary consumers of American popular culture, much of which produced music that was not to be sat and listened to, but danced to, shower-sung to, run to, eaten to, and shopped to.

Here was the bedrock for scholarly work that was not about analyzing music formalistically; it was about analyzing the lines between music and daily life, the ways music was controlled and distributed—in studying a modern music politics, it began to become clearer that it wasn’t just music that was political, so was everything surrounding its dissemination. And if record companies and radio stations (it’s amazing how antiquated those two terms already seem) had such influence in their production of music, it was not long before scholars turned their ears to the dissemination of sound on a higher level of power: that of corporations, governments, and deeply ingrained societal and cultural laws. This sort of study, it could be argued, started with Theodor W. Adorno’s critiques of mid-century popular music (and anything that resembled it) as consumerist debasement. It took others to actually look at the conditions of these musics and find that there were real creative communities there; that, as ever, it usually wasn’t the musicians that were most culpable in commercial hegemony (the definition of which has also changed continually). Attention had to be turned to commercial forces (wielded by those in power) and cultural norms (which are never imposed by only one person or community). Music, seen through this lens, now appeared as a minor cog in the wheel of sound. The entirety of music can be seen as one of Schafer’s “keynote” sounds, merely a bed of activity irremovable from the baseline of culture. Studying only music restricted us to studying a leisure activity in the face of mounting evidence that the study of sound was always already the study of politics and power, environment and experience. In studying music, we had been studying the actions of a minority of aesthetes; studying sound is, almost by definition, studying everyone.

* * *

I myself am a classical music composer of sorts. As such it is hard for me to think about this topic without turning to mid-twentieth century composer John Cage and his 4’33”.[1] In three movements, each marked “tacet” (which, in music, instructs the performer not to play), Cage stages a listening to environmental sound. Cage was not the first to create a “silent” music; he was preceded not least by Alphonse Allais’ Marche funèbre composée pour les funérailles d’un grand homme sourd (“Funeral March for the Obsequies of a Deaf Man”) of 1897. Cage’s piece, however, has no measures, no duration, and no proper title: four minutes and thirty-three seconds is simply the duration of David Tudor’s first performance. Since “tacet” instructs one to do largely what one was doing before the piece began, the only thing Cage really presents is the intervals between movements, with no instructions on how (or whether) to perform them. Without so many of the customary boundaries of a musical work, the onus for a ‘performance’ of 4’33” is not really on a performer; it is on the listener. And where Allais’ piece uses environmental silence in service of his concept (as laid out in the title), Cage does not use anything for anything–as musicologist and composer Martin Iddon put it to me, 4’33” “doesn’t represent silence; it is silence.” (Iddon)

Silence, of course, is not meant in any pure sense; the very impetus of the piece came from Cage’s personal realization that true silence is impossible to experience. But silence in the sense of Schafer’s “keynote sounds,” the “ground over which the figure of signals becomes conspicuous.” The debate about 4’33”’s status as an artwork has raged since its inception, mostly over vapid excuses for qualifications such as the lack of distinguishable pitches, or its indeterminate execution. But a solid argument against its being art comes from its mimetic relationship. Iddon spoke of 4’33”’s lack of representation; the idea that art must be representative comes from the Greek concept of mimesis. Mimesis was Aristotle’s main requirement for art as outlined in his Poetics, and translates roughly to something between imitation and representation, although neither are sufficient. Mimesis is what we are doing when we make art; it is also what we are doing when we receive art. Mimesis is the activity which separates art. Scholar Stephen Halliwell outlines Aristotle’s view thus:

[Aristotle’s] understanding of mimesis can be gathered from the distinction which he draws [against] citing the use of language for directly affirmative purposes — any use of language, that is, which purports to offer true statements or propositions about some aspect of reality. [Aristotle] implies what can best be described as the fictional status of works of mimesis: their concern with images, representations, simulations or enactments of human life, rather than with direct claims or arguments about reality. (Halliwell 71-72)

4’33”, then, falls short of art by failing to use images or lenses of any kind, by failing to represent; by instead making a direct claim about reality. But the fact that we can still refer to it and talk about it separates it slightly from daily life, and that is what is important: it is our decision to perform it as listening that separates it from daily life, not anything intrinsic about the work. What makes it akin to art (or art music) is the similarity of the attention it commands to that of art. Everything you can experience in the time frame is part of the piece. During a performance of 4’33” the very possibility for “environmental” sound is erased.

So perhaps sound studies comes less from a position of interpretation than from one of attention. Aesthetically, sound studies restricts the definition of music; attentively, it vastly expands it.

* * *

In Pauline Oliveros’ similar Deep Listening meditations, she usually begins with a series of instructions aimed at centering the body, rooting it with the earth so as to be fully ready for your next 20 minutes (or more) of intense listening. Tellingly, she specifically advises that one “notice where sounds impact the body.” A person’s ears are organs specifically designed for gathering sounds, but they are by no means its only method; the whole corpus is a resonating chamber, and the brain reaches into all parts of it to construct sound (this is one of the reasons your voice sounds so much different [and WORSE, UGH] on recording: you’re no longer hearing it through your body’s resonance). Oliveros takes the attention wrangled by Cage for 4’33” and informs it, hypersensitizes it, making a participant more aware that sounds are not things we hear, but things we feel, exactly as we feel changes in water pressure when submerged in it (the only difference being that our sensory organs evolved for air).

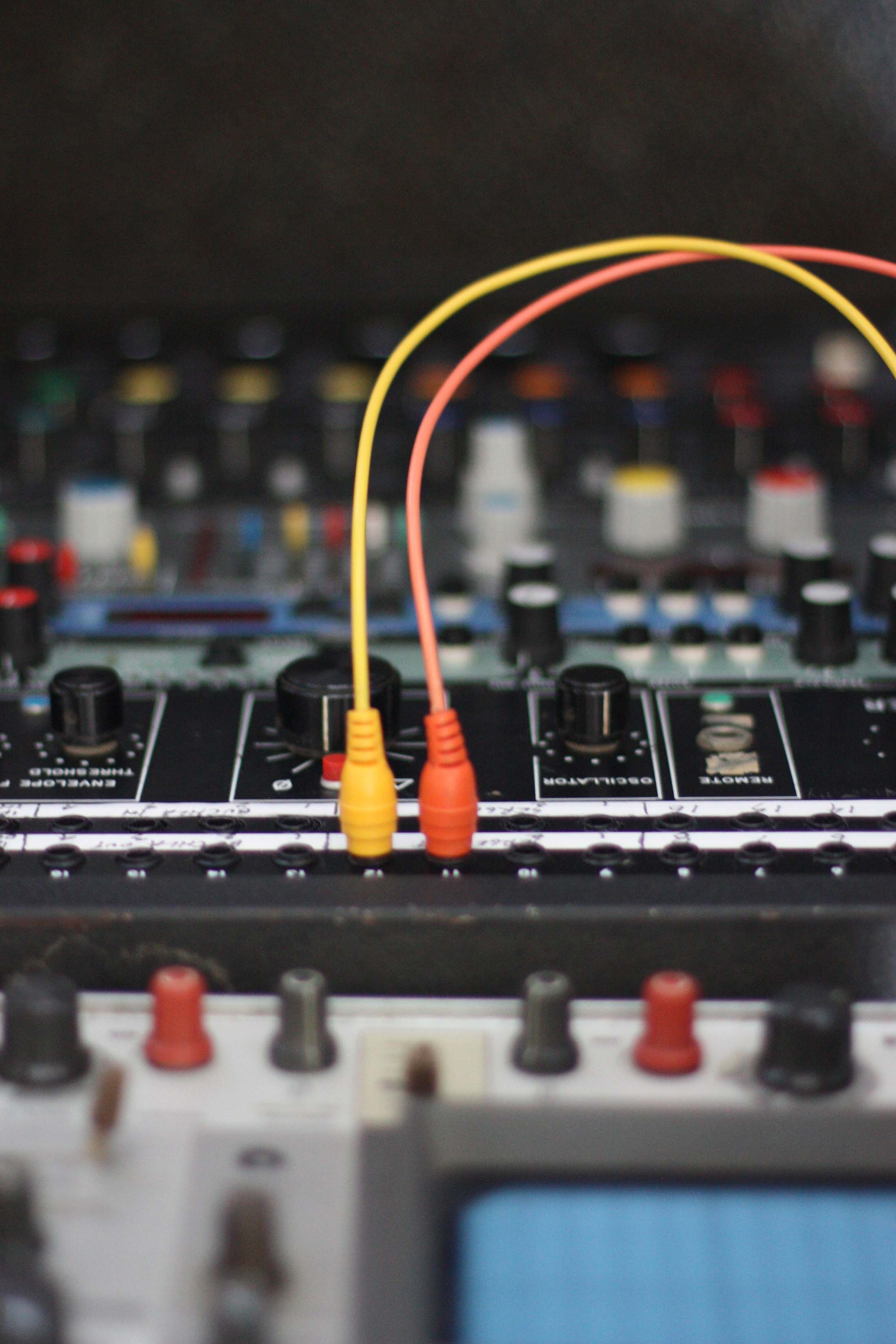

Another corpus that reoriented my body’s awareness of sound is the work of Alvin Lucier, an American composer known for his work with those less complex elements of sound: sine waves. Two pieces were specifically enlightening for me: his best-known work I am sitting in a room, and the more representative In Memoriam Jon Higgins.

Although listening to Higgins on headphones is a diverting experience, a different effect is achieved when heard in a room over speakers (or, obviously, live). Try it: put it on your best speakers. Turn it up (not too loud, but loud). Sit and listen for a while.

Lucier used pure wave oscillators in part because the waves’ clean edges, when put together, allowed him to make very distinctive, powerful beating sounds–these are the fast sounds that get more intense the closer the two pitches come to each other (before matching). If you are listening loud enough, you notice that this is not simply an aural effect. You can feel it all over your skull.

While listening to Scott Worthington perform the similar piece Homage to James Tenney in downtown San Diego a couple years ago, I noticed an even more pronounced effect: as I moved my head around in my personal space, the sounds changed. The beating became more or less intense as I changed my placement in the room, and thus the angles at which the sound hit my body. I realized, and I physically felt, that I was hitting my head against walls of sound, and pulling it back. (Try it; try walking around too.) The water analogy becomes more lucid when sound is not only something you can feel, but something you can touch. If in sound studies (and indeed, most music studies) the listener is the object, passively receiving sound, here Lucier demonstrates just how fuzzy that position can be.

Of course, music having superaural physical effects is not unique to, nor did it start with, American experimentalism. (Fans of heavy metal music, for example, have known about this at least since Blue Cheer’s ultra-loud cover of Summertime Blues in 1968.) Lucier, however, went a step further in 1969’s I am sitting in a room, a piece for himself as speaker, a tape recorder, and speakers. In the piece Lucier records himself speaking a monologue; he then plays the tape back, recording the playback. He then plays that tape back, recording it, etc. Because analog tape recording cannot possibly record all frequencies that sound to the ear, the quality of the recording degrades with each play as more data are lost. But as the quality degrades, the most resonant sounds in the room are reinforced as, due to their resonance and presence, they are recorded at a loud volume again and again. Over the 34 iterations of the recording, the intelligible speech eventually disappears, and what remains are the most resonant striae of that particular room’s acoustic spectrum, now ultra-reinforced, singing loudly and uninterrupted. This is achieved without any electronic manipulation other than recording and playback. Where In Memoriam Jon Higgins elucidates a human’s interactivity in the act of perceiving sounds, I am sitting in a room engenders an increased awareness of a human’s one-to-one affixedness to acoustic space when making sounds as well as when hearing them.

As I become more acquainted with each of the examples I have laid out so far, what strikes me is how unclear, in acoustics, the boundaries between sound and space, transmitter and receiver, signal and noise, [2] and, most unsettlingly, self and environment are. There is no sound a human (or anyone) can make that is not mediated by his or her acoustic situation; the impossibility of mediation gives that, for the purposes of sound production, a person and his or her natural surroundings are indistinguishable, one continuous entity. Apart from the usefulness of terms in conversation and study, the nature and condition of one’s attention to sound is so crucial to sound’s very existence as to be inseparable from it in any practical sense.

* * *

Music such as Lucier’s, Oliveros’, and Cage’s music can, like sound studies itself, be a way of moving past the formalism of much music, affording agency to listeners and citizens who may not have spent their lives building technical musical knowledge. They provide, especially in Lucier’s case, a felt physicality of sound that moves beyond the ear, both inwardly and outwardly. Listeners touch sounds for themselves; they do not receive pre-ordained structures, nor do they even sit and wait for two sounds to be the same as or different to each other. For semiologist Jean-Jacques Nattiez, though, this is not dissimilar to conscious or subconscious processes of perceiving and interpreting all musical signs, traditional or not. Nattiez writes,

The meaning of a text—or, more precisely, the contestation of possible meanings—is not a producer’s transmission of some message that can subsequently be decoded by a “receiver.” Meaning, instead, is the constructive assignment of a web of interpretants to a particular form; i.e., meaning is constructed by that assignment. (Nattiez 11)

For Nattiez, music, sounds, and signs are not transmitted from producer to receiver (or from musician to audience, police siren to bystander); they are always transmitted by a producer and constructed by a receiver (according to his experience with that sound or sign); an objective transmission cannot exist. These two processes are the poietic and esthesic, respectively. Esthesis is the “active perceptual process” in which each listener engages to interpret sounds. (Nattiez 12) Nattiez takes this process beyond individual sounds and attention to environment, saying that the theory implies

(a) a symbolic form (a poem, a film, a symphony) is not some “intermediary” in a process of “communication” that transmits the meaning intended by the author to an audience;

(b) it is instead the result of a complex process of creation (the poietic process) that has to do with the form as well as the content of the work;

(c) it is also the point of departure for a complex process of reception (the esthesic process) that reconstructs a “message.” (Nattiez 17)

Knowledge of symphonic form (or even of the boundaries of the work) is not the tool for esthesis: esthesis involves attending to these forms or not, depending on the listener. Listening is constantly constructing meaning. Moving away from semiotics: Christopher Hasty proposed a similar process for temporal perception in his exhaustive study, Meter as Rhythm. While traditionally meter in music is thought of as the strict partitioning of time, Hasty puts forth that meter is the phenomenon of a listener’s expectation of the future based on what has come before; it is the manifestation of the present. He, of course, puts it more poetically as:

a process in which the determinacy of the past is molded to the demands of the emerging novelty of the present. (Hasty 168)

Victor Zuckerkandl, a model for Hasty, wrote:

Without leaving the present behind me, I experience futurity as that toward which the present is directed and always remains directed. (Zuckerkandl 1956)

Spectral composer Gérard Grisey, thoroughly concerned with perception of time, wrote:

a series of extremely predictable sound events gives us ample allowance for perception. The slightest event acquires an importance. Here time has expanded. (Grisey 259)

In abandoning meter so extensively as to abandon form, 4’33” expanded the present (stretched it thin, some might say). Lucier’s music accomplishes this, albeit to a lesser degree. But this concept is not reserved for such experimental works. Grisey continues:

The relativity of perception suggests that, for the perceiver, there must be a halt in the traditional musical discourse, a point of suspension. One can find numerous examples of these suspensions in traditional music. (Grisey 268)

Grisey specifically cites mm. 58-62 of Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in G minor (K. 550), Mvt. I. (I highly suggest clicking that link.) These measures perform the same expansion of time and the present on a smaller temporal scale. Each repetition distances the past and clouds the future. In the context of sonata form, this is anticipatory and slightly terrifying. But with an esthesis differently nurtured, the repetitive figure slowly becomes a miniature keynote sound, an environmental bed for focused listening for minor changes. (This is easier to imagine if one imagines it continuing indefinitely.) The expansion of the present slowly disintegrates any chronological listening; instead of listening forward, one listens all-around. The longer it takes, the higher the potential for sounds to come from any direction in any manner; this is a concept of environment that affords listener agency. This saturated sensory situation is akin to dancing; instead of music, there is the world, and instead of your body, you have the ear (which, of course, is always your body).

When listening to the piece, this is obviously a fleeting event. But even within the context of Classical symphony, there are mechanisms for an intense, focused, but undirected listening that better perceives (and constructs) sonic reality: that we are immersed in a constant potential for making sound and listening to sound that pays no mind to where our bodies, or consciousnesses, begin or end.

* * *

Indeed, as we have known since Aristotle, sensing is always a perception, that is, a feeling-oneself-feel. . . But it is perhaps in the sonorous register that this reflected structure is most obviously manifest ,and in any case offers itself as open structure, spaced and spacing (resonance chamber, acoustic space, the distancing of a repeat), at the same time as an intersection, mixture, covering up in the referral of the perceptible with the perceived as well as with the other senses.

One can say, then, at least, that meaning and sound share the space of referral, in which at the same time they refer to each other, and that, in a very general way, this space can be defined as the space of a self, a subject. A self is nothing other than a form or function of a referral: a self is made of a relationship to self, or of a presence to self, which is nothing other than the mutual referral between a perceptible individuation and an intelligible identity. . . this referral itself would have to be infinite, and the point or occurrence of a subject in the substantial sense would have never taken place except in the referral, thus in spacing and resonance, at the very most as the dimensionless point of the re– of this resonance: the repetition where the sound is amplified and spreads, as well as the turning back where the echo is made by making itself heard. A subject feels: that is his characteristic and his definition. This means that he hears (himself), sees (himself), touches (himself), tastes (himself), and so on, and that he thinks himself or represents himself, approaches himself and strays from himself, and thus always feels himself feeling a “self” that escapes or hides as long as it resounds elsewhere as it does in itself, in a world and in the other. (Nancy 8-9)

* * *

I propose to paraphrase by saying that it is a question of going back to, or opening oneself up to, the resonance of being, or to being as resonance. “Silence” in fact must here be understood not as a privation but as an arrangement of resonance: a little–or even exactly…–as when in a perfect condition of silence you hear your own body resonate, your own breath, your heart and all its resounding cave. It is a question, then, of going back from the phenomenological subject, an intentional line of sight, to a resonant subject, an intensive spacing of a rebound that does not end in any return to self without immediately relaunching, as an echo, a call to that same self. While the subject of the target is always already given, posed in itself to its point of view, the subject of listening is always still yet to come, spaced, traversed, and called by itself, sounded by itself. . .

The subject of the listening or the subject who is listening (but also the one who is “subject to listening” in the sense that one can be “subject to” unease, an ailment, or a crisis) is not a phenomenological subject. This means that he is not a philosophical subject, and, finally, he is perhaps no subject at all, except as a place of resonance, of its infinite tension and rebound, the amplitude of sonorous deployment and the slightness of its simultaneous redeployment. . . (Nancy 21-22)

If, as Lucier made clear, you are inseparable from your environment; if you are a resonant body whose very self-awareness is articulated by signals constantly sent and received; if our concept of people as images rather than as resonant spaces in which we scramble to define a subject is wrong; if your attention to environment (in all directions, as only listening affords) is directly proportional to your experience of the present; if you are inseparable from your environment, as sound makes clear, then your environment is inseparable from you. When a listener is described with the appropriate agency and condition, the idea of sonic environment changes dramatically. As soon as attention is properly attuned, a personal performance of 4’33” begins. We are never passive receivers of sound. One is never innocent of what one hears. [3]

* * *

Despite sleeker cars, green initiatives, and the retreat of so much music into earphones, the association of modernity with themes of density, urbanness, pollution, and noise lingers, as much recent journalism confirms. While I would not say that sound studies becomes more relevant as our society proceeds, one can certainly make the case that sounds are becoming more multiple and more prevalent, not least in our consciousness of the concept of sound. As the world’s population continues to explode, more of us are jammed closer together; sound, however, does not obey smaller living spaces or desires for privacy. Although a certain amount of willpower can help, someone invading your eyes with an offense (you don’t have to look at it?) is still very different from someone invading your ears (you don’t have to listen to it?).

This idea came up in a conversation with musicologist Michael Uy about There Goes the Neighborhood, a study by William Julius Wilson and Richard P. Taub profiling four Chicago neighborhoods that have struggled (or in some cases, not struggled) to racially integrate. Predictably, members of different social groups often disagree on what an appropriate sonic environment consists of. Two examples from the neighborhood Dover, which was traditionally Polish and increasingly Mexican, paint a picture:

At a summer festival sponsored by a local church, someone teased a white woman about the polka music playing over the loudspeaker. She replied, “Yeah, I kinda like it, though. Over where my husband and I live, the air is always full of that Mexican music. Me and my husband, we put our speakers out on the back porch and just blast it. It’s like music wars over there.” (Wilson & Taub 58)

One young Latino male who had recently moved to Dover complained that his white neighbors had called the police to protest noise from a small backyard party. According to Luis, a car full of white police officers arrived and demanded that the party disperse. The host of the party barely spoke English and did not understand why he could not drink beer and listen to music in his own backyard. (Wilson & Taub 63)

In addition to racial and socioeconomic issues, loud music coming through walls often highlights disparities in age, and even lifestyle between members of otherwise the same group. Where Wilson and Taub examine myriad factors of cultural tension in neighborhoods, those of us in aural fields often focus on the sounds that people hear–or, the sounds that people have to hear. “Sounding” particular neighborhoods, cities, or cultures is a noble project undertaken today by ethnomusicologists and sound scholars alike, and the catalog is swelling. But I would like to once more turn the microphone back toward the individual, place it inside the self.

Geographers Vern Harnapp and Allen Noble, among many others, have pointed out that “Not only is there a grave danger for permanent hearing loss with sustained high levels of noise, just as real, though more insidious, is the psychological and stress damage. Continued exposure to high noise levels may result in high blood pressure, hypertension and more serious health impairment.” (Harnapp & Noble 219-220)

Although they speak largely of occupational hazards, it is not hard to imagine many modern urban residents’ sonic environments existing at or above these levels. I wonder if listeners have the power to affect this—not architecturally or civically, but aurally. How much can one’s attention affect sonic environment? How would performing 4’33” more often affect high blood pressure or hypertension? How would focusing on where a dog’s barks enter your body affect annoyance? How would attending to the physicality of two oscillating sirens affect anxiety? Is moving to a different corner of the room to experience them self-actualizing?

The neighbors are playing their music too loud again. Before you call the police, think: what are you doing to construct these sounds? What does their music say about you?

[1] Approximately 15 minutes (⅘ of the way) into this video, Cage himself can be seen performing 4’33” at a piano in the middle of Harvard Square.

[2] The term “noise” deserves far more attention than I intend on giving it here; for the most lucid and concise unpacking of this binary I have seen, cf. Iddon, Martin. “Siren Songs: Channels, Bodies, Noise”, In: Hall A (eds.) Noise, A Non-ference. New York: Qubit. 61-91.

[3] One issue I have not addressed here is the use of sound as a weapon. I do not mean to suggest that, in this situation, the victim is complicit in violence. They are not. The assertions I make here I limit to situations absent of physical pain and/or purposeful, forced sleep deprivation. These, however, are fruitful and necessary topics for further inquiry.

I would like to thank Prof. Alex Rehding for allowing mine to be the PREMIERE post on the SoundBlog. I’m looking forward to the interesting things that pop up here during the course of the seminar. Thanks also to Anthony Burr, John Hamilton, Martin Iddon, and Michael Uy.

Works Cited

Grisey, Gerard; trans. S. Welbourn. “Tempus ex Machina: A composer’s reflections on musical time.” Contemporary Music Review. 1987, 2.1: 239-275.

Halliwell, Stephen. The Poetics of Aristotle: Translation and Commentary. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1987.

Harnapp, Vern R. and Noble, Allen G. “Noise Pollution.” GeoJournal. 1987, 14.2: 217-226.

Hasty, Christopher. Meter as Rhythm. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Iddon, Martin. Personal correspondence. E-mail, 22 March 2013.

Nancy, Jean-Luc; trans. Mandell, Charlotte. Listening. New York: Fordham University Press, 1997.

Nattiez, Jean-Jacques; trans. Abbate, Carolyn. Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Wilson, William Julius and Taub, Richard P. There Goes the Neighborhood: Racial, Ethnic, and Class Tensions in Four Chicago Neighborhoods and Their Meaning for America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006.

Zuckerkandl, Victor. Sound and Symbol: Music and the External World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956.

Leave a Reply